Our last great scientific frontiers are to document the biosphere and “tree of life.” What compels my research is the knowledge that, for the first time in human history, we are losing more species through extinction faster than we can discover them. My research focuses on uncovering the patterns and processes of species formation in ants, specifically in Madagascar, and demonstrating how this knowledge can help us achieve a sustainable future. As part of this collaborative scientific effort, I created the annual Ant Course in 2001, AntWeb in 2002, the Madagascar Biodiversity Center in 2004, and the collaborative network IPSIO in 2016 (Insects and People of the Southwest Indian Ocean). I have published over 130 peer-reviewed articles and trained dozens of international graduate students in modern systematics and biodiversity methods, skills that enable them to use ants as an important indicator of biodiversity across the globe.

My lab's current research and related educational activities focus on (1) establishing ants as tool for conservation planning, monitoring restoration and climate change analyse in the Southwest Indian Ocean; (2) assembling the global ant Tree of Life; (3) building the research infrastructure and content of AntWeb and AntCat, the premier online sites for ant diversity; and (4) training the next generation of biodiversity scientists. Our focus is collection-based and highly collaborative, and we are driven not only by the need to do good science but also to ensure science aids society.

My lab's current research and related educational activities focus on (1) establishing ants as tool for conservation planning, monitoring restoration and climate change analyse in the Southwest Indian Ocean; (2) assembling the global ant Tree of Life; (3) building the research infrastructure and content of AntWeb and AntCat, the premier online sites for ant diversity; and (4) training the next generation of biodiversity scientists. Our focus is collection-based and highly collaborative, and we are driven not only by the need to do good science but also to ensure science aids society.

Insects and People of the Southwest Indian Ocean

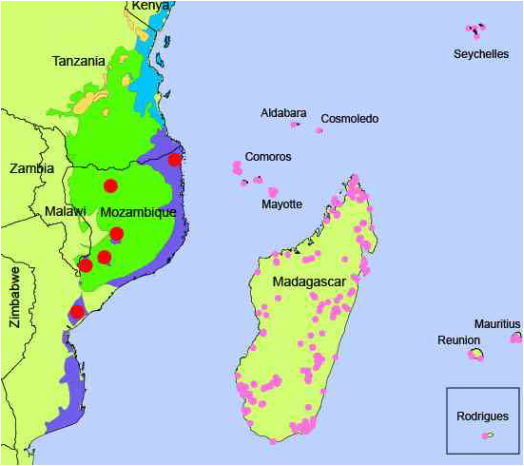

The southwest Indian Ocean (SWIO) islands of Madagascar, Comoros, the Mascarenes (including Mauritius, Reunion and Rodrigues), and Seychelles contain one of the highest concentrations of endemic and threatened organisms on earth. Isolation, geographic placement, varied geological histories, and environmental heterogeneity have all contributed to the bounty of endemic species. With a greater range of ages than most other island regions, the SWIO island system offers a unique opportunity to explore mechanisms driving the accumulation of restricted-range species at regional and local levels.

Since 1992, I have been working actively in the Malagasy region with support from NSF (four awards and two supplements), National Geographic (three awards), and a number of foundations and private donors. The goal of the project is to understand the origin and radiation of arthropods across the region and to use the results to improve the sustainability of these habitats. One of the largest arthropod inventory programs ever undertaken, it serves as a model for other efforts to inventory hyperdiverse taxa. We have demonstrated the feasibility of collecting, processing, and preparing large quantities of taxonomically-rich specimens across diverse, large-scale landscapes. A field crew has inventoried arthropods at over 350 sites across Madagascar and nearby islands using replicable and quantitative techniques. In Madagascar, a team of 15 parataxonomists sorts specimens to family or order, and has curated material for distribution to a network of 171 taxonomic collaborators, contributing to over 300 publications (PDF).

As for our work on ants, I lead a team that documents Malagasy ant diversity. We have taxonomically revised 471 ant species, and described 313 new ant species and six new genera. As part of our efforts to understand the evolution and biogeography of ants from the region, we have sequenced 28,000 specimens for the barcode CO1 gene, sequenced 13 nuclear genes from every major lineage, and created genomic libraries of seven genera.

As part of this project, I have advised MSc and PhD entomology students enrolled in several universities in the United States and at the university in Madagascar. With additional funding, three Malagasy students have obtained MSc degrees at San Francisco State University. The project in Madagascar has reached a broad audience through a variety of media, including articles in the New York Times: http://scientistatwork.blogs.nytimes.com/author/brian-fisher/.

Since 1992, I have been working actively in the Malagasy region with support from NSF (four awards and two supplements), National Geographic (three awards), and a number of foundations and private donors. The goal of the project is to understand the origin and radiation of arthropods across the region and to use the results to improve the sustainability of these habitats. One of the largest arthropod inventory programs ever undertaken, it serves as a model for other efforts to inventory hyperdiverse taxa. We have demonstrated the feasibility of collecting, processing, and preparing large quantities of taxonomically-rich specimens across diverse, large-scale landscapes. A field crew has inventoried arthropods at over 350 sites across Madagascar and nearby islands using replicable and quantitative techniques. In Madagascar, a team of 15 parataxonomists sorts specimens to family or order, and has curated material for distribution to a network of 171 taxonomic collaborators, contributing to over 300 publications (PDF).

As for our work on ants, I lead a team that documents Malagasy ant diversity. We have taxonomically revised 471 ant species, and described 313 new ant species and six new genera. As part of our efforts to understand the evolution and biogeography of ants from the region, we have sequenced 28,000 specimens for the barcode CO1 gene, sequenced 13 nuclear genes from every major lineage, and created genomic libraries of seven genera.

As part of this project, I have advised MSc and PhD entomology students enrolled in several universities in the United States and at the university in Madagascar. With additional funding, three Malagasy students have obtained MSc degrees at San Francisco State University. The project in Madagascar has reached a broad audience through a variety of media, including articles in the New York Times: http://scientistatwork.blogs.nytimes.com/author/brian-fisher/.

|

One goal of this project is to inform and aid conservation planning for the region. However, measuring and planning for the conservation of biodiversity remains difficult in the very places where these tasks are most urgent and critical, and information on the distribution of arthropods is scarce. In collaboration with colleagues (Kremen et al. 2008 Science), we showed conclusively that multi-taxonomic rather than single-taxon approaches are necessary to identify areas of greatest conservation priority. This analysis has immediate relevance in Madagascar, where the government is tripling its protected area network, and is readily transferable to other global priority areas. It represents an important scientific advance because most conservation planning is based solely on low-resolution, expert opinion-driven inputs encompassing a small number of species, and leads to plans that may not adequately protect a region’s full range of biodiversity. To disseminate our results more broadly in AntWeb, we developed a programmatic interface in R (in collaboration with Ropensci.org).

|

|

To increase our impact in Madagascar, we have launched in 2016 IPSIO (Insects and People of the Southwest Indian Ocean): A Network of Interdisciplinary Researchers Committed to Training, Sharing Tools, and Advocating for an Insect-Focused Approach in Conservation

We launched IPSIO because the current model of of individualized, solo research practiced by most entomologist is not having an impact in Madagascar. Entomologists have largely failed to have an impact on contemporary conservation issues because: a) their efforts are focused on individually chosen insect groups with little concern for applied outcomes; b) the rate we are understanding/documenting insects is so slow that it will take another 200 years before we make considerable progress with insects as a whole; and c) entomologists (compared to botanist) have not traditionally worked together on focused problems nor on a set of insects groups that can best address an issue. What if our efforts were not distributed thinly across the region on individually chosen insects but were instead focused on a strategic set to address problems with direct conservation outcomes.

We launched IPSIO because the current model of of individualized, solo research practiced by most entomologist is not having an impact in Madagascar. Entomologists have largely failed to have an impact on contemporary conservation issues because: a) their efforts are focused on individually chosen insect groups with little concern for applied outcomes; b) the rate we are understanding/documenting insects is so slow that it will take another 200 years before we make considerable progress with insects as a whole; and c) entomologists (compared to botanist) have not traditionally worked together on focused problems nor on a set of insects groups that can best address an issue. What if our efforts were not distributed thinly across the region on individually chosen insects but were instead focused on a strategic set to address problems with direct conservation outcomes.

Madagascar Biodiversity Center (MBC)

In 2004 I established a nongovernmental organization (NGO) in Madagascar to create a facility for entomological research and education. With land donated by the Minister of Education and support from private donations, the Madagascar Biodiversity Center opened in November 2006. The core mission of the Center is to uncover and protect Madagascar’s biological wealth and apply this knowledge to improve the quality of life in Madagascar. Through an active education, research, and conservation program, the Center fosters the promotion of a sustainable future for Madagascar. Training local scientists promises to be one of the most effective ways to ensure a long-term local commitment to conservation on this unique island.

The MBC includes training facilities for Malagasy students and provides an environment where Malagasy scientists can participate in conservation decision-making. I continue to provide financial and intellectual support to the MBC. In addition, the MBC serves as a logistical center for my research on arthropods in the region.

The center is focused on two large projects. With support from GBIF BID, the center is digitizing the entomological collection. With Support from CEPF, the Center is directing IPSIO (Insects and People of the Southwest Indian Ocean): A Network of Interdisciplinary Researchers Committed to Training, Sharing Tools, and Advocating for an Insect-Focused Approach in Conservation. IPSIO can be joined by contacting the Center or Brian Fisher.

The MBC includes training facilities for Malagasy students and provides an environment where Malagasy scientists can participate in conservation decision-making. I continue to provide financial and intellectual support to the MBC. In addition, the MBC serves as a logistical center for my research on arthropods in the region.

The center is focused on two large projects. With support from GBIF BID, the center is digitizing the entomological collection. With Support from CEPF, the Center is directing IPSIO (Insects and People of the Southwest Indian Ocean): A Network of Interdisciplinary Researchers Committed to Training, Sharing Tools, and Advocating for an Insect-Focused Approach in Conservation. IPSIO can be joined by contacting the Center or Brian Fisher.

Ant Tree of Life: a comprehensive evolutionary tree for the world’s premier social organisms.

At some point during the Cretaceous the first ant walked the Earth. This progenitor would give rise to one of the most ecologically dominant animal lineages on the planet. A fundamental question relevant to the evolution of sociality in general is whether this first ant was a blind, subterranean creature, or a big-eyed, generalist surface forager, similar to something that might visit your picnic today. The key to this puzzle lies in understanding major evolutionary events in the lineages of ants still with us today.

The primary objectives of the AToL project are to uncover the relationships among the major lineages of ants using molecular and morphological data; to estimate divergence times of principal clades; and to use the resulting phylogenetic and temporal framework to analyze the evolution of key biological traits in ants. This is a collaborative project involving PI Phil Ward (UC Davis) and co-PIs Sean Brady and Ted Schultz (Smithsonian Institution) and myself.

Results from the Ant AToL project (Brady et al. 2006 PNAS; Ward et al. 2010 Syst. Bio.; Ward et al. 2014 Syt. Ent.; Brady et al. 2014 BMC Evolutionary Biology; Ward et al. 2015 Sys. Ent.; Blaimer et al. 2015 BMC Evolutionary Biology; Ward et al. 2016 Zootaxa) have yielded useful insights into relationships among the major ant lineages. We find that basal relationships among the major ant lineages remain uncertain, as several alternate scenarios are equally well supported. In 2016, we began using both ultraconserved elements (UCEs) and an anchored phylogenetic approach to better understand key events in ant evolution.

The primary objectives of the AToL project are to uncover the relationships among the major lineages of ants using molecular and morphological data; to estimate divergence times of principal clades; and to use the resulting phylogenetic and temporal framework to analyze the evolution of key biological traits in ants. This is a collaborative project involving PI Phil Ward (UC Davis) and co-PIs Sean Brady and Ted Schultz (Smithsonian Institution) and myself.

Results from the Ant AToL project (Brady et al. 2006 PNAS; Ward et al. 2010 Syst. Bio.; Ward et al. 2014 Syt. Ent.; Brady et al. 2014 BMC Evolutionary Biology; Ward et al. 2015 Sys. Ent.; Blaimer et al. 2015 BMC Evolutionary Biology; Ward et al. 2016 Zootaxa) have yielded useful insights into relationships among the major ant lineages. We find that basal relationships among the major ant lineages remain uncertain, as several alternate scenarios are equally well supported. In 2016, we began using both ultraconserved elements (UCEs) and an anchored phylogenetic approach to better understand key events in ant evolution.

AntWeb and AntCat

AntWeb is the world’s largest online database of images, specimen records, and natural history information on ants. The project’s goal is to create a comprehensive virtual museum for a group of animals with tremendous importance in the environment. AntWeb has the potential to improve biodiversity protection by incorporating ants, which provide a much finer scale perspective on habitat diversity than birds and mammals, into global conservation planning. While AntWeb focuses on specimens and images, AntCat provides access to taxonomic references and current classification. AntCat is maintained by the taxonomic community,

What would it be like to live in a world where you could know the name of any animal, even the ants beneath our feet? And not just the name of each ant, but what it looks like, its habits, its distribution, whether it is endangered, whether it has been introduced or is a native species? What if you could do this without visiting a museum or library? What if you could do this even if you lived in the tropics where most diversity occurs? And what if we could use this knowledge to help protect habitats, monitor ecosystems, and reconnect human health to the health of the natural world?

In other words, what if the museum was not a warehouse of dead creatures, but a portal for understanding the world around us? To achieve this requires a rethink of the analog museum. By digitizing collections, we will connect the vast amount of knowledge stored in museums to global conservation and sustainability efforts. Digitization will help create a baseline index of life that then can be used to protect the world’s remaining biological wealth. Digitization is linked to the future of life on earth, to society’s stability and well-being, and to the wise stewardship of our planet.

With support from NSF, we launched the World Ant Tour in 2012 to capture images of all ant species: http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/18368213. Our team has imaged over 17,000 ant types; we now have digital representations of 75% of all described ant species. We are now seeking funding to image 95% of all ant types in the next years.

AntWeb demonstrates that improving collaboration and access to taxonomic resources is an effective way to accelerate efforts to understand global biodiversity. By adopting an open access model and providing access to the world’s ant types, this project is responsible for creating a sea change in the demography of ant taxonomy.

This project moves museum information from the cumbersome and traditional analog format into the digital age. It moves taxonomic knowledge out of the hands of select Northern Hemisphere museums and into the hands of interested participants everywhere, a feature especially valuable to those who reside in the diverse tropical regions far from wealthy nations and their scientific collections. AntWeb delivers a wealth of scientifically rigorous but also broadly appealing biodiversity information on diverse groups like ants to both the taxonomic community and the public. It enables local experts to participate in the study of diversity and taxonomy. It helps to move insects into a position of central importance in the conservation arena. And for many members of the public, it provides the first opportunity to access reliable and detailed information on this diverse and fascinating group of animals.

What would it be like to live in a world where you could know the name of any animal, even the ants beneath our feet? And not just the name of each ant, but what it looks like, its habits, its distribution, whether it is endangered, whether it has been introduced or is a native species? What if you could do this without visiting a museum or library? What if you could do this even if you lived in the tropics where most diversity occurs? And what if we could use this knowledge to help protect habitats, monitor ecosystems, and reconnect human health to the health of the natural world?

In other words, what if the museum was not a warehouse of dead creatures, but a portal for understanding the world around us? To achieve this requires a rethink of the analog museum. By digitizing collections, we will connect the vast amount of knowledge stored in museums to global conservation and sustainability efforts. Digitization will help create a baseline index of life that then can be used to protect the world’s remaining biological wealth. Digitization is linked to the future of life on earth, to society’s stability and well-being, and to the wise stewardship of our planet.

With support from NSF, we launched the World Ant Tour in 2012 to capture images of all ant species: http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/18368213. Our team has imaged over 17,000 ant types; we now have digital representations of 75% of all described ant species. We are now seeking funding to image 95% of all ant types in the next years.

AntWeb demonstrates that improving collaboration and access to taxonomic resources is an effective way to accelerate efforts to understand global biodiversity. By adopting an open access model and providing access to the world’s ant types, this project is responsible for creating a sea change in the demography of ant taxonomy.

This project moves museum information from the cumbersome and traditional analog format into the digital age. It moves taxonomic knowledge out of the hands of select Northern Hemisphere museums and into the hands of interested participants everywhere, a feature especially valuable to those who reside in the diverse tropical regions far from wealthy nations and their scientific collections. AntWeb delivers a wealth of scientifically rigorous but also broadly appealing biodiversity information on diverse groups like ants to both the taxonomic community and the public. It enables local experts to participate in the study of diversity and taxonomy. It helps to move insects into a position of central importance in the conservation arena. And for many members of the public, it provides the first opportunity to access reliable and detailed information on this diverse and fascinating group of animals.